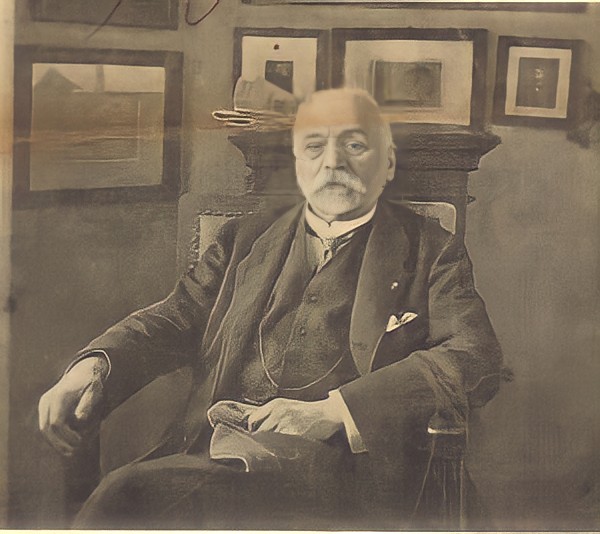

Yet it will still be held in Budapest, from 15 to 20 May, for the 10th International PEN Festival. World Congress. (The French consider it a ll. because they had already celebrated the 10th anniversary of International PEN in London in 1931, although that meeting was not a world congress). In a negotiated settlement between the government and International PEN (and especially the French PEN president Benjamin Crémieux), those who have been excluded are being taken back and those who have left are resigning. (However, Sándor Márai still does not take a seat on the congress organising committee. His letter of resignation survives). Temporarily – at the request of Jenő Heltai, Ferenc Herczeg and Dezső Kosztolányi(!) – Albert Berzeviczy, president of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and former minister, takes over the presidency of the Hungarian PEN Club. He is the host of the Budapest Congress. He introduces guests at the reception for Governor Miklós Horthy.

The list of invited guests of honour, some 270 foreign delegates and participants is impressive. The best known are:

England (Chesterton, Drinkwater, Galsworthy, Masefield, Shaw, Wells; the founder of International PEN, the elderly Mrs Dawson Scott, is unable to travel to Budapest due to illness).

Austria (Roda Roda, F. Salten).

Belgium (Maeterlinck).

Czechoslovakia (K. Čapek, E. B. Lukač).

Denmark (K. Michaelis, Pontoppidan).

Finland (Koskenniemi).

France (Duhamel, Gide, J. Green, Maurois, Romain Rolland, Valéry, Jules Romains).

Netherlands (Jo van Ammers-Küller).

India (Rabindranath Tagore).

Yiddish-PEN (Warsaw) (Schalom Asch).

Germany (Th. Däubler, G. Hauptmann, A. Kerr, Ernst Toller, F. Werfel).

Norway (J. Bojer, Knut Hamsun, Sigrid Undset).

Italy (Bontempelli, Marinetti, Croce, Corrado Govoni; Pirandello signed up but cancelled).

Palestine (the Hebrew translator of Madách and Ady, Avigdor Hameiri, originally known as Albert Feuerstein-Kova in Hungarian).

Romania (O. Goga, L. Rebreanu).

Sweden (S. Lagerlöf).

The first meeting will be held on 17 May in the hall of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. President Berzeviczy conducts the meetings mostly in French, but also in English and German when the occasion arises. The delegates will speak in French, English and German. John Galsworthy, President of International PEN, opens the meeting in English (he apologises for not repeating his opening speech in French and German) and immediately commits both the organisation and the meeting to non-politics and literature as art. There can be no party and state politics here, he says. Signed by 22 writers from the US, Belgium, Canada and Austria, they address a “Sozo” to “all governments of the world”: protesting against the imprisonment of writers for political or religious reasons and the oppression of prisoners. The Romanian delegate, who was one of the first to speak, was greeted with great applause when he announced that the Hungarian chapter of Romanian PEN had been founded in Cluj (with Miklós Bánffy). UK (and International) PEN Secretary Hermond Ould reports that there are now 51 PEN organisations in 36 countries, and highlights the work of Gyula Germanus and John Knittel in Egypt.

How do we serve peace without politics? – this is the basic request of the Congress. And a source of fierce debate.

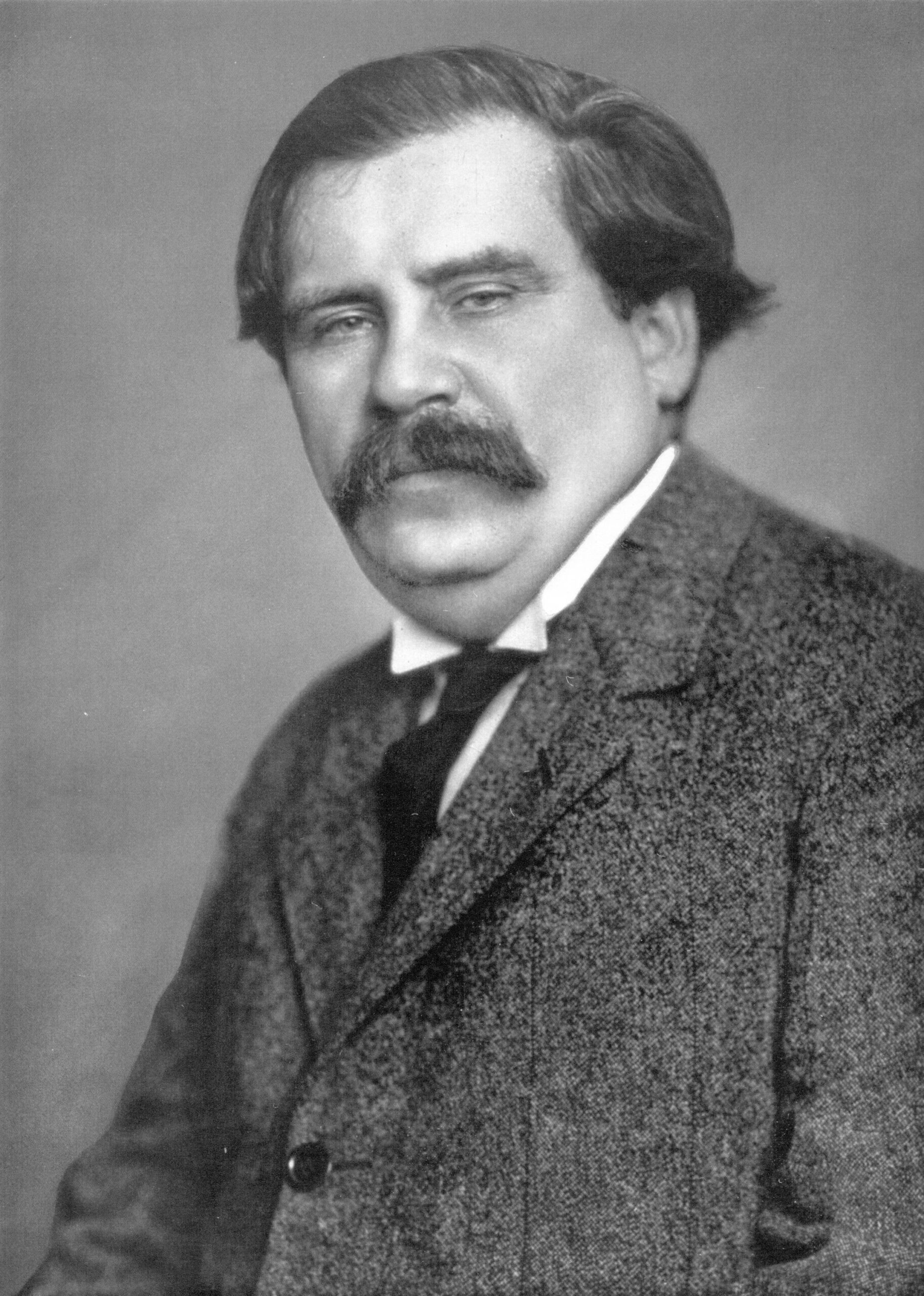

Ernst Toller (Germany) passionately points out that spirit and politics are inseparable. Well, Joyce’s Ulysses has just been banned in England, along with several other books, and Remarque’s film has just been banned in Germany. Aragon is also persecuted in France (although writers there have formed a united front in defence of Aragon). Remarque’s works cannot be published in Italy either. In Hungary, too, the translator of Octave Mirabeau was sentenced to four months and Victor Margueritte’s novel (Le compagnon – The Companion) was banned. (“What’s going on in Russia?” they shout.) Following Goethe, Toller stresses that what we do is more important than what we write.

The Italian Marinetti is truly outraging the audience. It is a different interpretation of the principle that PEN and politics should be two separate worlds. He quotes a Latin saying: ‘If you want peace, prepare for war’. Don’t talk about peace here. Protect it instead! (With a bed? – someone interjects sarcastically).

On behalf of Hungarian PEN, Gyula Illyés also speaks out against censorship, book confiscation and the press trial, for freedom of the press and freedom of thought. It proposes that all such offences should be recorded and publicised by the London PEN Centre. György Sárközi (Hungarian PEN) also supports Toller and Illyés. The intellectuals are right to oppose governments and pseudo-patriotism, he says. No one should be persecuted for their beliefs, he demands.

Jules Romains (France) also turns against Marinetti and demands a non-violent literature. Let there be neither better nor worse in literature. Anyone who deviates from it is excluded from French PEN.

Béla Zsolt (Hungarian PEN): ‘Are they talking about minority protection? The intellectuals are minorities too!” International PEN calls for a body to register and publish offences against intellectual freedom.

Karin Michaelis, a Dane: “We would not tolerate persecution of spirit workers in Denmark”.

Mihály Babits, speaking on behalf of the Hungarian PEN, gave a pensive, reflective lecture, the most memorable moment of the World Congress. What can the writer do for Peace? He is not a man of direct action. Can only write? Can’t his words show a national bias? And even if it is free of it, could it not be influenced by some other, more terrifying worldview? Can you calculate the impact of your words? The best never compromise, and writers have never been persecuted for their brave writing as they are in Europe today. The writers of “Little Hungary” never gave in to armed terror and fear: we preserved our faith in peace and the brotherhood of peoples. But they can still stifle the writer’s word. Cenzura. PEN has no better task than to protest against any curtailment of literary freedom. But can we be satisfied with mere words, with parlour pacifism? A real writer is not satisfied with just that. It depicts life (even the horrors of war) with authenticity and dispassion. But is this the best peace propaganda? Literature, which has only a slow impact, could take a great step towards peace if it would confront the dangerous conception of facts and emotions and restore the authority of reason and morality. We must inspire hope in our youth. Is selfishness and cruelty a law of nature? We must embrace the religion of Spirit and Truth. We must lead nations, not follow them. Morality and Justice. These are the two supreme judges. In the name of morality we can even criticise morality, in the name of truth we can even criticise truth. The Englishman Ernest Raymond raises the eternal question of PEN congresses: the question of language. He suggests that they should ask the League of Nations for advice: which language should be made the sole and compulsory working language of International PEN? Hungarian PEN (Frigyes Karinthy) gives the answer: the language that belongs to no one, because it is artificial. Esperanto.

Afterwards, a new “Steering Committee” is elected, consisting of the Frenchman Crémieux, the Polish Juliusz Kaden Bandrowski, the German Hans Elster and the Dutchman W. M. Westerman.

This marks the end of the 10th edition of the World PEN Congress.

But this is also the end of Albert Berzeviczy’s “honorary” presidency. The writer, poet, literary translator and literary historian Antal Radó, the eminent Dante scholar and author of a 5-volume history of Italian literature, will be the new leader of the Hungarian PEN Club. executive chairman until 1939, then chairman until 1944